Margins are the new budgets

By Dann Berg

Published or Updated on

Photo from Usplash

Photo from Usplash

An attendee at a recent NYC FinOps Meetup raised an interesting question to the group: how do you handle setting budgets and tracking spend against those budgets? I realized that for all my years as a FinOps practitioner, I had never worked for a company that had a traditional “budgeting” process.

At a previous company, we had experimented with budgets, but it felt like forcing an antiquated accounting practice into a fast-paced cloud-native environment. It proved more trouble than it was worth, so we found different practices that provided the same benefits as traditional budgeting but that were more befitting to our particular business.

FinOps is not just about saving money in the cloud. It’s also a way to update old financial practices to take advantage of the variable-spend nature of the cloud.

Most infrastructure accounting practices were built and honed when all servers and network equipment was on-premise in a data center. Senior leadership and the board would review and approve a budget for servers and other infrastructure, and then not think about it until the next budgeting cycle. Engineers were forced to work with what they had, because lead times for new hardware was typically several months.

But with cloud computing, an infinite1 amount of infrastructure is now available instantly at the stroke of a keyboard. This also means that spend shifts from an easily budgeted capital expenditure to variable operating expense. Not only that, but nearly every engineer has the power to spin up new capacity (and thus cost the company more money).

So what does the old-school budgeting process look like when it is completely re-thought for the cloud? And how should cloud-native SaaS companies2 think about infrastructure spend?

The answer is a robust margin-based process, which I hope will provide a lodestar for FinOps Practitioners working on upgrading their own day-to-day practice.

The anti-budget ah-ha moment

When I started my first dedicated cloud-cost role, one of my first projects was building visibility into individual teams’ spend. To approach this, I grouped cloud spend by team, and worked with the top ten highest-spending teams on the list. I built dashboards for these teams, highlighting each’s spend broken into useful categories. These dashboards were available to view any time, emailed to relevant team members once a week, and reviewed together monthly in scheduled cloud-cost meetings.

Once that system was built, it felt like the obvious next step was to set budgets for each teams’ spend. We had decent historical data, as well as context around roadmap items, so it made sense to set spend budgets for upcoming months and then measure each team against those targets.

We set this all up, but problems arose the first week of the month after launching these new budgets. One of the teams had unexpected growth in this first week that caused our forecast for them to blast way above budget. We immediately started working with the team to identify the cause of the cost spike. It turns out we had onboarded a big new customer, and that’s why costs had grown. We discarded the outdated old budget number, and instead set our expectations for spend at the new forecast level.

The next month, something similar happened with a different team. After days of investigations, we came to a similar conclusion: the previously-set budget was no longer a good indicator of team-level success for this team this month.

The new process created tons of new work (investigations), and the only insights we discovered was that the budgets should have been higher. The business didn’t care if a team’s spend was higher than our set budget, as long as the costs were justified. The budgets we set could easily become outdated, and it happened constantly.

We needed to cut out the middle-man (the budget) and build a system that could immediately tell us if cost-increases were justified.

A move towards application efficiency

Each engineering team owned one or more applications, or microservices, that fit together into the larger SaaS-application picture. This was an important piece of the investigation puzzle when faced with team-level cost increases, since it pointed us to the exact location of the culprit.

As an example, if the cost increase was coming from an application that’s main purpose was to ingest logs, we could tell if the cost increase was justified by looking at the number of logs ingested. Did the number of logs ingested increase (due to a new customer, or an existing customer increasing use) alongside the cost increase? If so, the cost increase itself mattered less than if we were remaining efficient as we scaled to support this additional usage.

This was our ah-ha moment. The team spend dashboards were interesting, but were still once-removed from the actually useful information.

The next phase of cost visibility wasn’t setting budgets for each team and then tracking spend against those budgets. Instead, it was building application efficiency tracking into these dashboards, so we could instantly see whether there was usage to match cost increases or not.

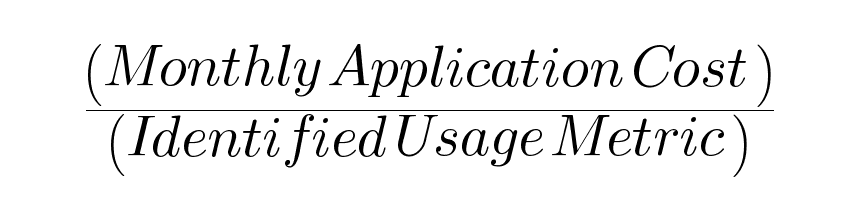

We worked with each team to identify a single metric that each application’s costs should scale against, and then divided total costs by that metric.

Once we built this additional view, it became our main cost-visibility metric. We still kept an eye on total team spend, but as long as efficiency remained within certain bounds, we didn’t need to launch any one-off investigations.

So, what about budgets?

Most cloud-native companies are realizing that it’s actually counter-intuitive to try and fit SaaS engineering teams into a legacy budgeting process. It creates too many false alarms, and wastes too much engineering time performing detective work on cost anomalies that almost always end up being justified.

Not only is this true at a team/application level, but also at the larger company-wide level.

Often, Finance departments believe that a traditional budgeting process is necessary for a mature company. From my experience, it’s the exact opposite. Instead, I’ve come to the conclusion that older, legacy companies should be working to update their “classic” budget process to fit more within an agile, margin-based system.

From a Finance perspective

Companies can benefit from different FinOps strategies at different stages of their businesses. A 10-person company and a 500-person company can both be “startups,” but each will be focusing on adopting different FinOps practices. The FinOps Foundation calls this “crawl,” “walk,” and “run."

Personally, my favorite time to join a company is around the 600-employee mark, after a Series C or D raise. It’s at this point that a company can really benefit from a dedicated, full-time FinOps practitioner, as it’s working to transition from move-fast-and-break-things pace to a more sustainable and optimized cloud strategy.

Usually at this stage, a company’s Finance department3 has grown in headcount, and is focusing on maturing its accounting practices beyond the foundational practices that has served the company thus far. They’re starting to improve existing reports and create new analyses that will help the company make even better strategic decisions.

When it comes to cloud-cost forecasting, there’s always room for improvement. Especially since it is one of the top, if not the top, expense for many SaaS companies.

Generally, these forecasts are calculated from a top-down perspective. Meaning, you start with total revenue, remove cost centers, and subtract cost of goods sold (COGS). It’s “top-down” because you start with the total numbers in each category. To forecast future spend, you add a growth rate4 to these totals.

This forecast is standard accounting practice, but is limited in terms of the value it can provide back to Engineering. When monthly growth is relatively linear, this forecast is not something that needs much attention. But as soon as you have a month or two with abnormal growth, you realize how this limited view doesn’t actually provide you with any answers.

Illuminating forecasts using margin

Sometimes your actuals are way above forecast, but it’s a reason to celebrate, not panic. It can mean you closed a big new customer, or had an unexpected spike in paid usage. When looking at the numbers, it’s less important to know if you’re above forecast — instead, when you’re above forecast, you want to know if that’s good or bad.

Often, that’s two steps:

- Analysis shows that your actuals are above forecast

- Perform discovery into why you’re above forecast

It’s that second step that typically takes the most time to complete, and often involves multiple people on different teams. What we really want is a way to tell, at a glance, if our above-forecast spend is justified or not.

One way to instantly tell, at least at a SaaS company, is by looking at overall gross margin. If spend was over forecast, but gross margin stayed flat or improved, then the extra spend is justified5.

So, how do budgets still fit in?

If you’re working at a company that already has a complex budgeting process that’s deeply engrained in multiple parts of the business, it probably doesn’t make sense to campaign to dissolve the system completely.

Instead, as a FinOps Practitioner, you can focus instead on building your own analysis that allow you to avoid interacting with these budgets as much as possible. There may be several upstream dependancies that rely on these budgets, there’s no reason to disturb these processes.

You can provide enormous value in your current role without engaging these budgets at all. Instead, focus on building a robust margin-based view of the business, which will provide more value to the business than if you just acted as the “Keeper of the Budgets.”

If you’re working at a SaaS startup, however, it’s likely that the business doesn’t yet even have a budget process (which has been my professional experience thus far). If you have senior leadership that is pushing to implement budgets, because it’s a way to build a more “mature” practice, you should feel empowered to push back.

Figure out exactly what value these budgets are meant to achieve, and if there’s a superior way to execute that value. Chances are, maturing your marginal analysis will serve the company better in the long run.

And if you’re not at a SaaS company, there may be no way to avoid budgets for certain parts of the business. You may have large business units that don’t, in any way, contribute to revenue, and these business units need to be monitored for spend. If this is the case, try to identify which business units can benefit from a margin-based analysis, and which ones can’t. Apply the right methodologies where appropriate.

Once you start operating at scale, you realize that it really isn’t infinite, but those nuances are better covered in a separate post. ↩︎

In this article, I’m going to be focusing on SaaS (software as a service) companies primarily, but will touch on other business types towards the end of the piece. ↩︎

My roles have all been part of the Engineering department, rather than as part of Finance. Therefore, my view here is as an outsider looking in. If any finance people reading this are shaking their heads in disagreement, feel free to message me with any corrections. ↩︎

In the most basic form, this growth rate can just be a percentage growth each month, based on past-months’ growth. More advanced versions can take into account things like revenue projections, sales projections, product roadmap items, etc. ↩︎

Obviously, there’s some extra nuance beyond this simple rule. Margin deterioration may also come from the sales side. And a flat margin might be reason to investigate if the company expected it to increase. But as a general rule, at SaaS companies, margin is a solid indicator of justifiable spend growth. ↩︎