Photo from Usplash

Photo from Usplash

This is a written version of the talk I gave at the FinOps X 2022 conference in Austin, Texas called “And Then There Was FinOps: Creating and Scaling your Cloud-Native FinOps Practice.” The conference happened for me at a rare between-jobs moment, where I had just finished working at Datadog the week prior, and I wasn’t starting my new job at FullStory for another couple weeks (I wrote more about that decision here).

That presentation has now been posted on YouTube in full, so you have the choice to watch/listen instead of reading. Or do both, if the mood strikes.

Given the point in my career when I gave the talk, this post is focused on the things I was thinking about at the time: how I approach building a FinOps practice at a new company as an individual practitioner, and the lessons I’ve learned from past experience.

The imagined audience is twofold: individual practitioners looking to do something similar, and companies interested in building out this practice. But I also think the information has a potential wider appeal, as anyone can pick and choose bits and pieces that work for them.

How I think about FinOps

At its core, I believe FinOps can be narrowed down to two action areas:

- Decrease the money feedback loop

- Decrease price of cloud infrastructure

The other area of focus for FinOps is using infrastructure cost data to enable better-educated business and product decisions, but I’ll be mostly talking about those two action areas in this post.

The money feedback loop

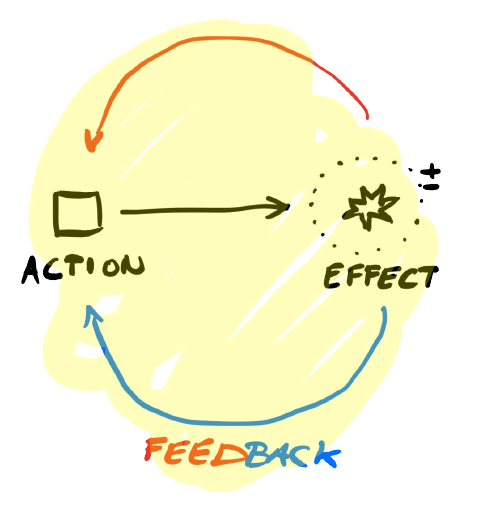

When an engineer makes an infrastructure change, there are a few types of feedback that happen immediately. Worst case scenario, something went wrong and there’s an outage. Maybe things worked well and a bug is gone, or the site runs faster.

There’s a nearly instantaneous feedback loop for things like reliability, availability, speed, etc. Deploy the wrong code, and within minutes you might see degraded service or even a full outage.

At most companies, however, the money feedback loop is significantly longer (if it’s there at all). Typically, it’s the Finance department that’s fielding the cloud invoice, and it’s up to them whether they want to even connect with Engineering.

Sometimes the money feedback loop can be as long as 45 days — the invoice will arrive in the middle of the month, showing the cost impact of a change made at the beginning of the previous month. Tracking down the who, what, why becomes a whole production.

As a FinOps Practitioner, your goal is to reduce that money feedback loop as much as possible. It might not be instantaneous, but you should shoot for between three days to a week (a delay in billing data reporting on the cloud provider side prevents the loop from getting much smaller).

There are two tools in your tool chest that help here: cost dashboards and alerts. Are engineers able to view their costs? If so, are they actually looking? Do you have alerts set for certain types of anomalies?

The money feedback loop is all about providing visibility into an area of the business that’s not always presented to engineers. Not to slow progress, but to create a culture where engineers are aware that their actions have monetary reactions.

The price of cloud infrastructure

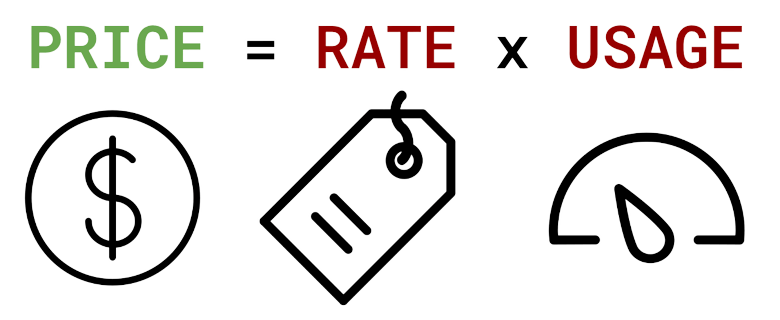

At its core, the price of cloud infrastructure is an extremely simple formula:

price = rate x usage

That means that if you want to lower the price, you have two levers that you can pull: rate and usage. Everything you do is in favor of one of those two levers.

Lowering Rate

Examples of lowering rate include: negotiating enterprise discounts, private pricing agreements, and savings plans/reservations/commitments. In order to have the greatest impact, actions that lower the rate should be managed in a centralized fashion.

“Centralized” meaning that a single team or person should be in charge of this area on behalf of the entire company. The last thing you want is for each individual team to be responsible for negotiating deals with the cloud provider!

Likewise, you’ll get higher reservation coverage if all your savings plans/commitments are purchased on behalf of the entire company, rather than on a per-team basis. Purchasing these commitments at the payer level will allow them to be applied wherever they’re most needed.

Lowering Usage

Unlike lowering rates, lowering usage is best tackled in a decentralized fashion. This means that a centralized FinOps person/team can help organize, plan, and prioritize the work, but actual execution is often best done by individual engineering teams.

Lowering usage often includes architecture changes, right-sizing of instances, optimizations, or other engineering work. Engineers are going to know their applications better than any outsider, so it’s up to the FinOps group to support this work as best as they can.

It’s also important to keep in mind the larger business goals when prioritizing cost-optimization work. The FinOps team should not be always pushing work to reduce costs — instead it’s important to enable teams (and the wider business) to decide if it makes business sense to work on new features or cost-optimization work.

It probably makes sense to build and run a program around cost-optimization work, where you can build up a queue of opportunities while engineers are working on growing the company, and can quickly execute if it makes sense for the business to focus on margin.

Starting from the beginning

With that framework in mind, let’s dive into how I approach building a FinOps practice from scratch at a cloud-native company. This is based on my experience at Datadog, as the first hire focusing exclusively on cloud costs, as well as my current position at FullStory, which is much the same thing.

There are six independent phases that I think about individually. These phases are:

- Listen and observe

- Visibility, visibility, visibility!

- Reduce those rates

- Think bigger picture

- Automate and grow team

- Tackle larger problems

There is a rough order to these phases, but by no means do they need to happen linearly. In fact, you should plan to run many of these phases concurrently, and in whatever order makes sense for your business.

Let’s take a closer look at each.

Phase 1: Listen and observe

As with any new job, your initial task is to listen, observe, and take in as much information as you can. Every company operates slightly differently, and is in a different stage of their FinOps journey. You’ve got to understand the foundation you’ll be working with.

When you’re the person responsible for cloud spend, there are a few areas you should explicitly be observing.

Existing tagging strategy

Tagging is the practice of applying labels to individual cloud resources in order to identify and attribute spend. There’s a good chance that the company you’re joining has an existing strategy around this infrastructure tagging, but the maturity of that tagging practice can vary widely.

When you first join a company, there are several tagging-related observations to make: How much of the infrastructure can be attributed based on tags? How are those tags being applied? How hard would it be to modify? Who set the past rules for tagging? Do people currently think of tagging within the company as successful or unsuccessful? Why or why not? Is there an expectation for you to change or improve the tagging strategy? If so, in what way?

Current spend visibility

Who can see costs, and what does that view look like? Where do engineers currently go to get cost feedback (if anywhere)? What about managers or team leads? VPs? The executive team?

Likewise, what does spend visibility currently look like for the Finance department? Are they currently getting any spend visibility from Engineering to compliment the monthly invoice? Are they happy with that visibility, or is there any additional information they could use?

Existing goals around spend & optimization

There’s a reason that you were hired for this role. What is that reason? There’s a good change that that reason is going to vary depending on who you’re talking to. As you meet people across the company, ask each of them for their own personal interpretation of why your role exists in the first place.

Decisions around architecture and upcoming work

It’s also important to figure out where engineering decisions are being made, and start listening in. This could mean joining a Release Management meeting or Slack channel, reading OKR documents each quarter, or even meeting with teams directly.

You should work towards building a high-level view of all engineering work that incurs cost. This will seem overwhelming at first, but just continue listening and observing (and taking notes!) and eventually the bigger-picture view will all start coming together.

Stakeholders & executive sponsorship

In a FinOps role, you should think of both engineers and your coworkers in Finance as your customers. As you settle into the role, figure out which specific people across these two teams have a particular stake in your work. Also think about who else besides your manager is a decision maker with regards to your priorities?

At a certain point, you’ll likely need to roll out a larger program that spans across the entire engineering department or even across the entire company. This will be much easier if you have executive sponsorship. Which member of senior leadership seems to care the most about cost visibility and optimization? Make sure you take note of who they are, and work with them when it comes time to make the larger moves.

Phase 2: Visibility visibility, visibility!

Visibility is one of the most important aspects of FinOps, as it’s the foundation upon which everything else is built. Phase one includes understanding what visibility looks like today. Now it’s time to improve that view.

There are two levels of visibility to work towards. Once you build the first level, it’s time to build the second level on top of it.

Visibility Level I

This is the base level of visibility, allowing you to view costs by different cost centers. Do you know how much teams are spending? Do you know how much certain applications cost to run?

Visibility Level I may take the form of a dashboard, which might allow an engineering team to input their team name and view all the costs that are associated with them. It may be useful to isolate by product, so that the team can view their compute, storage, and data transfer costs separately to try and spot unexpected trends.

An advanced Level I includes a methodology for identifying and attributed shared costs to the appropriate teams. A simple version of this methodology might be to take all shared costs and attribute them to each individual team based on percent of total spend. A more advanced way might be to monitor usage metrics tied to groups in order to calculate a more accurate percent. Either way, you need to figure out 1) which costs should be shared, 2) who they should be shared with, and 3) how much should be attributed to each cost center.

Visibility Level II

Visibility Level II is where you add both context and meaning to these costs. This means joining billing data with business metrics in order to calculate efficiency.

Let’s say you have an application that ingests logs. If you take those costs divided by the number of logs ingested, you’ll be able to expose the application’s efficiency over time. With the second level of visibility, you want to do this in as many places as possible.

Some businesses are able to identify a single Key Performance Indicator (KPI) for their entire business. More often than not, having a single KPI is not possible. Instead, you’ll want to break the business into smaller chunks and then identify the metric(s) that those costs should scale against. Then, you can set efficiency goals for those different parts.

Additional Visibility

One other area you should check on, when it comes to cost visibility, is Finance. Figure out how they’re categorizing different types of costs, processing the cloud provider invoice, forecasting spend, etc.

What sort of visibility do they have into detailed billing data that compliments the monthly invoice? Is there any way that visibility can be improved? Might there be a better way to forecast month-over-month growth if you were to take engineering projects into account?

Phase 3: Rates

As I mentioned in The Price of Cloud Infrastructure, efforts around reducing rate should be done in a centralized manner. That is to say, there should be either a single person, or a small group of people, working on any areas that might impact the price of cloud resources.

The first rate-related area you’ll likely work on is reservations. Depending on the cloud provider, these might be called something different: AWS has Savings Plans and Reserved Instances, GCP has Committed Use Discounts, and Azure has Reservations. All of these are instruments for reducing the rate you pay for compute usage.

First of all, if a reservation purchase needs to be made, make it as soon as possible. It’s a good early win to start saving the company money. For the longer-term strategy, you’ll need to figure out how to properly analyze current reservation coverage, set goals around where you’d like that coverage to be, and decide how often this needs to be re-evaluated.

For example, at Datadog we performed this analysis on a weekly basis. We’d calculate our On Demand spend as a percent of our total Compute spend, and set goals for that metric. If On Demand was too high, we’d purchase additional reservations. If it was too low, we’d either hold off on making an additional purchase, or we’d allow some existing reservations to expire.

Figure out this larger strategy, and who the key stakeholders are that need to approve the strategy and each purchase. Then get to work executing it.

The other piece of rate reduction is any enterprise discount agreement that your company might have with the cloud provider. Often, this takes the form of a top-line discount in exchange for a minimum spend commit over a certain number of years. Sometimes, these discounts can be more granular on a product-by-product basis.

Figure out what expectations people have for your role in these conversations and negotiations. If you’re able to push cloud providers for deeper discounts, then push.

Phase 4, 5, 6: Bigger picture, automate, and expand

Everything outlined above is no small task. In fact, there’s a good chance that once you get this up and running, it will take up the majority of your time. If you’re not careful, time will fly by and you’ll continue doing the same thing in the same way week after week.

That’s why it is important to start thinking about the bigger picture as early as possible. If this is a full-time job for a single practitioner, what might you be able to do with a second team member? What if it was a team of five? The FinOps Foundation website can be an excellent resource for fleshing out your vision.

Don’t just think about the answers to these questions — write them down. Create a document outlining your view for a team roadmap, and start socializing it. Partner with people in the Engineering and Finance departments to help you write the document.

This is a difficult step, but vitally important. Once you have alignment on the longer-term FinOps function within the organization, you can make sure that all the work you’re doing today tracks towards that goal.

This is also the point at which you should think about automating anything that you haven’t yet automated.

With a clear bigger-picture vision in place, it’s time to start executing on some of the larger programs. This might mean executing a company-wide re-tagging initiative if it’s needed, or simply becoming deeper embedded with Product to help enable smarter feature decisions using detailed cost data. The specific expanded function of your team is going to vary based on your specific company’s needs, but it should all work towards the bigger picture vision you’ve helped develop.

Growing your team

At Datadog, we organized our team’s work into sprints, even though our projects didn’t always fit the Agile method very well. For regular engineers, finishing a ticket means that the work is done, and you can move on to another ticket. But with FinOps, sometimes finishing a ticket is only the beginning.

Often, you’re tasked with digging into a particular cost spike or anomaly. It might take a week or two to put together a well-researched analysis. This document is shared, and people find it quite useful. In fact, this new view is something that would be useful on a regular basis.

In this way, new FinOps work can often turn into recurring work. And there’s only so much recurring work that a single employee can do before 1) their week is completely full and 2) there’s no time to work on expanding the practice.

Once you’ve automated all that you can automate and your weeks are still full, it’s time to think about growing the team.

As such, there are two different types of ways to grow the team. The first is hiring someone to take over some of these existing recurring processes. This employee should have the ability to quickly get up-to-speed, and then take this recurring work to the next level.

The second way to grow the team is based on a wishlist function of your team. If you’ve defined a bigger picture vision (Phase 4) then there will be things that you wish your team could do if it were larger. One way to jumpstart that growth is to hire a practitioner to come on board and kickstart that new ability.

If you’re a FinOps Practitioner looking for your next opportunity, keep these two needs in mind as you’re interviewing. Does the hiring company want you to take over some existing work, or build out an entirely new function? Figuring this out will help you speak to your specific strengths in each area during the interview process.

A career in FinOps

I want to end this post with a few personal opinions on building a career in FinOps, both for individual practitioners as well as companies trying to build (and retain!) a successful FinOps team.

Be a part of Engineering. When I said this at FinOps X, I think it might have upset a few of the Finance-side FinOps Practitioners in the audience. But it’s sticking with this advice. When FinOps is a function of Engineering, you’re much better integrated into the business and it’s easier to get things done. An engineer talking to another engineer is intrinsically different than Finance talking to an engineer.

Also, the pay is better on the Engineering side, if that’s something that’s important to you.

If you’re reading this from the Finance side, consider exploring the Engineering side of the house for your next role. Start looking now at what skills you’d need to build up in order to make you a competitive candidate. It might not be as much as you think.

Make sure career progression is clear… and don’t re-invent the wheel. If you’re a company’s first FinOps hire, there might not be a clear career progression defined yet. You might be wondering if it’s best to borrow from the Finance career progression, or Engineering, or to borrow from different places to make up your own FinOps progression.

My advice is to just use Engineering. Don’t give it any more thought. If your company already has a defined engineering career progression, use that. Make sure it has two tracts: one for individual contributors (ICs) and one for management.

Rent the Runway has made their engineering ladder public, and it can serve as a solid foundation if your company doesn’t have a good internal document for you to use.

Always be learning and growing. As a hiring manager, you always want to make sure people on your team are learning and growing. This is fairly easy in the FinOps space, since the industry is still so new, and fresh ideas are coming out every day. But it’s still important to be explicit in this growth mindset.

Help the wider community. There’s a wider FinOps world to be a part of. Join the FinOps Foundation and get active in the Slack. Attend a Meetup. Start writing and publishing everything you’ve learned in the space. Even if you’re new, there’s always someone that’s newer than you.

Also, as soon as you put the words “FinOps” in your LinkedIn profile, you’ll start getting a ton of messages from recruiters. Every time you get a message, ask for the role description and salary band. If the salary band is low, let the recruiter know. They may still be able to find someone to hire in their desired range, but that sort of salary feedback will help the wider community make more money.